Mehmed-beg Achmed Pasha was disgruntled. This was not a terribly unusual occurrence; indeed his intimates and friends, of which very few survived, would claim that he was never gruntled (if that is a word; well it should be, if it is not). Baker Pasha had insisted that there should be a “proper parade” as the army left Avlonya. The

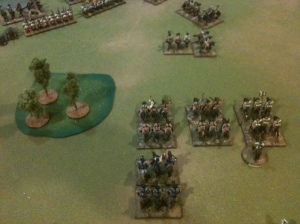

The Sipahi move past the staff. They should be out scouting, but they would get lost.

Sanjak’s nature was much more inclined to lead him to a quiet departure in the the depths of the night, preferably with some nice dense fog to mask his movements. To his disappointment, fog was a rarity on the sunny Adriatic coast, and the rules for the military seemed to be different. They seemed to require bands, loud noises and bright sunshine to do anything, and “subtlety” was not a word that seemed to appear in the military lexicon.

So there he sat, oppressed by the fact that they were going to have to march across

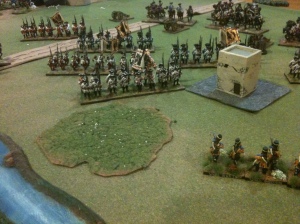

Nizam march past, lead by the band, and followed by disgruntled Janissares

Europe to stage a pointless battle, and now he had to watch a bunch of idiots walk around in lines, just so that, as Baker Pasha put it “they could begin in the right state of mind”. Mind you, the man had proved himself to be rather good at this sort of thing (as shown by the two rather well armed and LARGE men who now accompanied the general, Faisel had done well there) so Mehmed-beg was not going to gainsay him.

They waited in the warm sunshine as the army began its march past. Baker saluted each unit smartly, the Sanjak waved his fly whisk, Faisel glowered. Di Tripodi was with them also, but seemed to be wrestling some intractable supply problem with his Janissary staff officer. Idly casting his ear in the direction of their animated discussion, he discovered that something dreadful had happened to some shipment of bulgur wheat. As the Sanjak had a strongly held belief that the worst thing that could happen to bulgur wheat was him having to eat it, he sat back with a smile, and waved Faisel over.

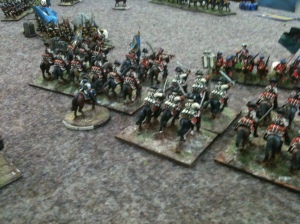

Crveni Lopov leads the local levies past. At a discreet distance, because they would steal the horses if they were closer

“I hear that some of the supplies have been ruined. Do you have any idea how such a dreadful thing might have happened?”

Faisel replied, with a straight face “Excellency, as I understand it, your palace cook’s nephew has a post in the army commissariat. The cook apparently made clear, at a family gathering, your views on bulgar wheat. The young man acted on his own initiative from then on.”

“Ah” replied the Sanjak “could you make sure that they both receive a suitable reward?” He did not bother to add the word “discreetly” as he had never known Faisel to be indiscreet.

“Of course, Excellency. While I have your attention, some dispatches have arrived from the west. Herr Fugger in Hamburg writes that the funds were received, and that he has already disbursed some to Kyrios Papandriou. Kyrios Papandriou writes thathe has arrived in Trèves, and that he was successful in his purchases; some eight parts of the coopers, stave makers and briners in the west of Trève and its surrounding areas have been sold to him, or an interest in the larger ones purchased. The news of this expedition seems to have had a very depressing effect on prices.”

The Sanjak waved his fly-whisk, acknowledging yet another salute. “Excellent” he said.

Faisel hesitated. “Excellency” he said “I did think we were going to burn those places. Ummm.. why are we buying them?”

The Sanjak grinned at his secretary. “Because, Faisel, even that optimist Baker thinks we are not going to win this one. If he does not think so, I am going to agree with him. Seems likely that we will be driven off before we can do much damage. So.. we buy those businesses for cheap…. and then sell them when we return home.”

Faisel’s face cleared. “Sell them? not keep them, Excellency?”

The Sanjak answered briskly. “I am already starting a new career as a soldier, which I never wanted to do. Starting one as a a meat packer at my age I want to do even less. I doubt the gentle Kyrios wants to run businesses so far from home. We’ll split the money, and be happy with it.”

Faisel nodded, and withdrew, watching the parade end and the baggage begin to move by.

—oOo—

Mehmed-Beg looked around at the assembled crowd. They had marched almost across Europe; with promises of huge pigsties full of gold Baker Pasha and Di Tripodi had restrained the most egregious of the looting while crossing notionally “friendly” states (more on the grounds that they were going to have to come back that way, rather than some excess of humanitarian zeal) and the army had arrived in the electorate of Trève.

Of course, completely forewarned, the Cardinal-Elector’s army had been more or less waiting for them, so very little destruction of swine-related industry had occurred before the two armies came into contact.

Thus this meeting. Apparently it was tradition for the leaders of both armies to gather, to arrange things like the time the battle would start, and the rules (!?!) that would be followed. Or at least Baker and Di Tripodi informed him, with the nodding agreement of von Frechting. For someone whose career had started with by knifing people in the back, and had more or less continued that way, with the odd detour into poisons and lethal livestock, this attitude was incomprehensible to the Sanjak and also to Faisel who had followed a similarcareer plan, but if that was what was to happen, they would let it go. They both agreed on the need to look like good civilised, rules following individuals before they subverted the rules of the game.

So here they stood, in the pale morning light. His own group, himself, Baker Pasha, Di Triodi, von Frechting, and some others, with Faisel standing in the background. The group from Trèves was interestingly broken up, he thought. There were a cluster of similarly uniformed officers (he had been told that the most gorgeously uniformed one was Count de Toulouse-Laurtrec who was notionally the commanding general; however his stance indicated deference to the two other groups); there was another group of three men, one gorgeously attired and languid to the point of sleeping, another older, heavy individual, and a third, younger man whose glowering looks and glares around betrayed either a terrible temper or a terrible hangover. Possibly both. The third group was just two men, one in red cleric’s robes, and the other in an outlandish uniform that would fit right in with the most gayly attired sipahi. A glance at the man in the red robes told who was really in charge, but he seemed content to let others do all the work.

The discussion started amiably enough, with Baker Pasha speaking with Count de Toulouse-Laurtrec in french (the Sanjak thought) presumably the necessary courtesies and arrangement of whatever-it-was they thought should be arranged. Mehmed-beg looked around at the town of Pluwig, behind him, and idly wondered which bits of it he owned now, and how on earth he was going to stop those particular bits being too thoroughly looted. A change in voices, and indeed languages, from the group made him snap back around, and he saw things had changed.

The choleric man, shaking off the hand of the heavyset individual on his arm, was snarling at Baker Pasha, in a language that the Sanjak did not know or recognise. Baker Pasha was turning red, with an alarming whiteness around his lips. Mehmed-beg glanced at Di Tripodi, who responded “English. The aggressive bloke is insulting Baker, calling him .. some form of deviant maybe.. my English is not that good, but we should break it up, I think.”

Mehmed-beg, agreeing, waved Faisal forward to escort Baker Pasha, and looked around again, telling Di Tripodi to conclude the meeting. He noticed that Count de Toulouse-Laurtrec had stepped back, and his staff looked embarrassed; he noticed also that the Cardinal and his man seemed to be in the dark also. The red clad cleric spoke, and gestured to his man; to the Sanjak’s surprise, the approached him, not Count de Toulouse-Laurtrec.

Faisal moved forward to escort Baker Pasha, as the gayly clad man with an eyepatch spoke with the Sanjak and Di Tripodi, first in french, at which both of them shrugged, then in Italian (with an accent of the Genoese docks, which made the Sanjak smile in reminiscence of previous bad times on hearing)

“Signori“, the man began “my name is Rochefort, and the cardinal asked me to discover from you what is happening, if you would be so kind?”

The Sanjak waved “It appears that your excitable gentleman” indeed, the fellow was now completely red in the face and stomping his foot in excitement, gripping the hilt of his sword “has some sort of personal history with my general. I am unsure what the matter is.” Though, Mehmed-beg admitted to himself, he could hazard a fair guess. “Can you translate for us, Di Tripodi?”

“Burgess ain’t one of mine” muttered Rochefort, causing a raised eyebrow from the Sanjak.

“Si” answered the chief-of-staff ” as there was a pause, Burgess apparently being out of breath, and maybe inspiration. The his eye fell on Faisal, who was guiding Baker Pasha backward, and his excitement hit a whole new level.

“You scurrilous arab bastard, I have been looking for you for years!” Di Tripodi translated the rant, now aimed at Faisel. “Give me my money immediately, you cheat! I was stuck in debtors prison in Malta for a month because you cheated me. I demand my money, or satisfaction immediately!”

“You cleaned that up a bit, Signor, I think.” said Rochefort, out of the corner of his mouth. Di Tripodi shrugged, and nodded in agreement.

“Faisal is unlikely to give the man money” observed the Sanjak “Satisfaction is…?”

“A duel” said Rochefort. “The whole swords in the dawn light thing. Stupid as can be.” He looked at Burgess, who was now having to be physically restrained by his two companions “Though it looks like we might not have to wait that long…”

Faisal joined them, leaving Baker Pasha in the hands of his staff. Mehmed-beg looked at him and asked in italian “Faisal, are you going to give that man money?”

Faisel raised an eyebrow “No, Excellency”. He looked at the other group. Burgess had stripped off his coat, and drawn his sword, and was stamping and swishing it trough the air. They were being approached by the languid individual.

Rochefort looked at Faisal “You’ll probably have to fight him then” Faisal shrugged. Rochefort added, as he noticed Faisal’s unarmed state “You can borrow my sword, if you like, its fairly sharp.”

Faisal took the offered weapon, and balanced it in his hand. “Many thanks, effendi” he said quietly.

Rochefort looked at the approaching dandy, and spoke out of the side of his mouth “How much did you take him for?” he asked.

“Effendi, we played dice in a tavern in Malta, some years ago. Unfortunately, his dice appeared to be lacking the 3, 4, 5, and 6. So sad. He lost to me a nice large purse of gold, enough for a good Arab stallion, and two mares”.

Rochefort whistled, while di Tripodi and the Sanjak grinned. “Nice, very nice, good job” Rochefort said, as they all turned toward the dandy, who indicated that the duel was to take place right here and now, and he was acting as a second for Burgess. Rochefort shrugged, said he would act for Faisal (rather to the surprise of everyone) and promised to explain the rules. The dandy moved away, nodding to Burgess, who prepared himself.

Rochefort turned to Faisal. “I am supposed to explain the rules to you, Signor” he said.

Faisal raised his eyebrow. “Rules effendi? There are rules?”

“One” replied Rochefort. “You kill him, and then we are done here.” He nodded, bowed slightly, handed Di Tripodi his scabbard and swordbelt and said “Keep the sword, I hate the thing.” Then he smiled as he moved away.

Faisal nodded all around than then walked toward Burgess, swishing the sword in his right hand. Which was fairly odd, the Sanjak mused to himself, because Faisal was left handed…

Ten feet from Burgess, as the man was just taking up his pose, Faisal did something complicated and too fast to see with his left hand, and started withdrawing back toward the Sanjak, who turned to BakerPasha and Di Tripodi and said quietly “Time to leave.”

They both looked a little confused, but not half as much as Burgess, who was contemplating the knife hilt sticking out of his chest in deep confusion. The Sanjaks’s party was just mounting as Burgess collapsed forward, surrounded by his party, some of who looked confused as well, a couple more starting to look outraged.

As they rode off, Mehmed-beg noticed that the Cardinal-elector and Rochefort looked neither. The cardinal seemed to be hiding his mouth behind his hand, and Rochefort was clearly grinning, though facing away from the rest of the group. The Sanjak cheerily returned his wave as they rode off.

And now there would be a battle to fight.

The ottoman forces put forward a screen of a mass of irregulars, with the core of their regular troops and artillery forming up around the outskirts of Candia.